Cyclic Performance of BBR and Cubic

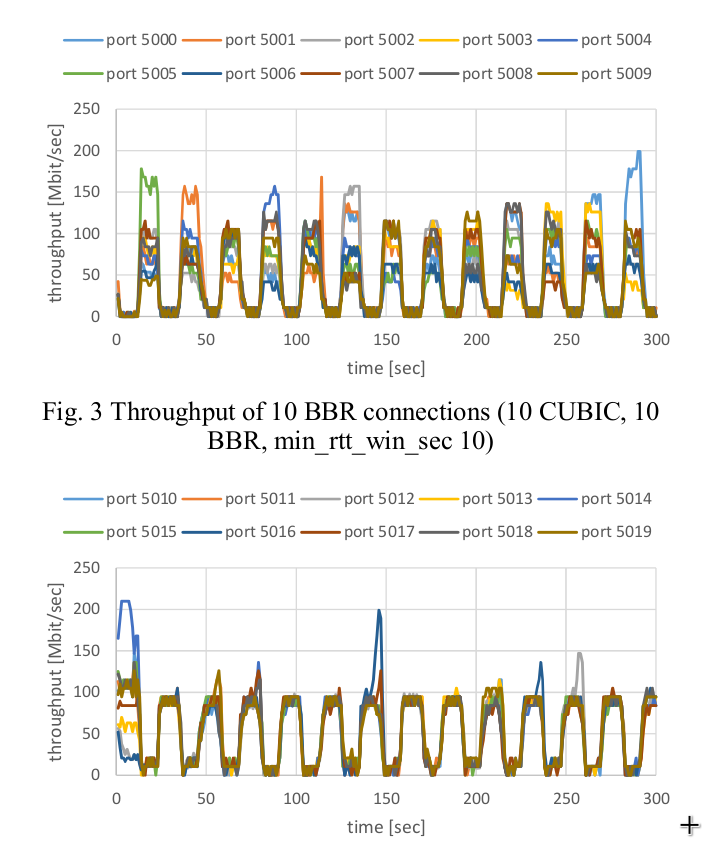

In the paper “Cycle and Divergence of Performance on TCP BBR” by Miyazawa and Sasaki, the authors show that when BBR and TCP are competing on the same bottleneck, their ‘share’ of the bandwidth will not be consistent. Rather, the dominant flows will cycle between cubic and BBR, where first BBR will dominate the flow for 10 seconds as cubic backs off, and then cubic will dominate the flow as is steals bandwidth during BBR’s rtt probe phase. We aim to confirm this in our panaderia environment. This cyclic behavior shown in this paper is depicted here:

In this, the ‘troughs’ or the low regions of the BBR flows (whose throughput is shown on the top image) correspond to the peaks of the throughput of the Cubic flows (shown on the bottom image). This behavior is bad. Congestion protocols should aim to provide stable and reliable behavior, but this is indicating a very unstable throughput that ranges from roughly 0 mbit / second to a 100 mbit / second. This is a huge amount of variation.

Validation

Given such a drastic result, we aimed to recreate this in our panaderia test environment. We did this by combining 3 queueing disciplines:

Netemwith a huge bufferNetem is used to create the delay in the network. Because everything here is a local network with roughly 3ms rtt, we add a small (10ms) delay to the network. The bandwidth for this queue is roughly infinite as we only want to see drops at the TBF bottlneck.

TBF80mbit token bucket filter with a large queueThis, combined with the next token bucket filter create the 80mbit bottleneck. To avoid the token bucket filter burstiness, we use a second token bucket filter with a smaller bucket.

TBF80mbit token bucket filter with a smaller bucket, and $225{,}000$ byte queueThe BDP in this network is $bandwidth * delay$, so for our network, it is roughly $80 mbit * 30 ms = 300{,}000 bytes / second$. So, we set the buffer of the bottleneck to just below 1 BDP, at $225{,}000 bytes$. This ensures that, because BBR allows up to 2 BDP of data to be inflight (and thus 1 BDP of data to be in the queue), the queue can be saturated by the BBR flows.

Token bucket filter config

sudo tc qdisc del dev enp3s0 root

sudo tc qdisc add dev enp3s0 root handle 1:0 netem delay 10ms limit 1000

sudo tc qdisc add dev enp3s0 parent 1:1 handle 10: tbf rate 80mbit buffer 1mbit limit 1000mbit

sudo tc qdisc add dev enp3s0 parent 10:1 handle 100: tbf rate 80mbit burst .05mbit limit 225000b

# sudo tc qdisc add dev enp3s0 parent 100:1 handle 1000: tbf rate 80mbit burst .05mbit limit 1000mbit

tc -s qdisc ls dev enp3s0

# https://netbeez.net/blog/how-to-use-the-linux-traffic-control/

# https://wiki.linuxfoundation.org/networking/netem

Results

As the prior paper suggests, we also see cyclic performance between BBR and Cubic flows.

The cubic flows (shown blue and green), and the bbr flows (red and orange) roughly stay in lock-step. As one group goes up, the othe will be throttled. This rotates roughly every 10 seconds, which corresponds to BBR’s round trip polling phase. This makes some sense, as BBR will back off during this phase, and thus allow cubic to ramp up and steal bandwidth. So, during the ramp up phase, there won’t be any available buffer remaining. This will cause BBR to plateau at a much lower throughput than its fair share.

In progress

calculate the loss rate.